Pancreatic surgery: evolution and current tailored approach

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is an uncommon type of cancer, the incidence of which has been on the rise worldwide, likely correlated with an increased incidence of obesity. Pancreatic cancer rates are highest in North America and Europe, where the frequency of its occurrence puts it in the eighth place (1,2). Although it is not very common, its significance lies in the fact that it is most often diagnosed in the late stage of the disease, it is almost always fatal, surgical treatment is rather complex and there is no adequate adjuvant treatment. Moreover, it is the only type of cancer in Europe of which increased mortality is anticipated in 2014 (3). Five-year survival rate in Europe and North America is around 6%, which makes it the fourth cause of death according to cancer mortality statistics (1,2). However, within the 10% of patients who have been diagnosed in the early, localised stage, the 5-year survival rate rises to 25% (4,5).

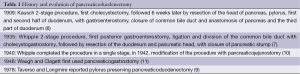

There has been immense progress in surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer patients since Kausch and the first pancreaticoduodenectomy of periampullary tumor (6), Whipple and his modification of pancreaticoduodenectomy in the 1930’s (7), Priestley and the first successful total pancreatectomy reported in 1944 (8), and Traverso and Longmire with pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1978 (9) (Table 1). Despite the initially high mortality and morbidity following surgical treatment (12,13), with the development of surgical technique and concentration of patients in high-volume centres, as well as with improvement in perioperative care, the rate of morbidity and mortality following pancreaticoduodenectomy has dropped to acceptable levels. Morbidity and mortality following total pancreatectomy have also become more acceptable, as well as long term outcome with better blood glucose regulation and exocrine insufficiency management which has been made possible by developing novel insulin formulations and pancreatic enzyme supplements. Improved management of endocrine and exocrine insufficiency following total pancreatectomy and the discovery of novel clinical entities, such as IPMN (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm), have revived what was once a rare surgery, with an increased number of procedures and widened indications for surgical treatment.

Full table

Despite its complications, curative resection is the single most important factor determining the outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (14). Surgery remains the principal treatment for pancreatic cancer and offers the only chance for cure (15,16).

Complications of pancreaticoduodenectomy

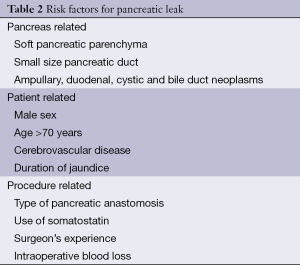

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is indicated for patients with neoplasma of the head of the pancreas, ampullary, duodenal and distal bile duct neoplasms. It is also performed for chronic pancreatitis and rarely for trauma. Although high mortality rate approaching 25% and morbidity rates up to 60% (12,13) were initially related to pancreaticoduodenectomy, in the last few decades there has been a significant decline in mortality rates which is now 3-5% in highly specialized centres (17-19). On the other hand, there are still numerous possible postoperative complications related to pancreaticoduodenectomy and morbidity rates are as high as 30-60% (20-24). Most common local complications are delayed gastric emptying with prevalence of 8-45% (25-30), pancreatic fistula with reported rates from 2% to 22% (20,23,24,30-34), infectious complications, most commonly intra-abdominal abscesses, with prevalence from 1-17% (30,35) and hemorrhage. Postoperative bleeding occurs in 3-13% of patients (5,17). Hemorrhage within the first 24 hours is result of the inadequate hemostasis at the time of surgery, a slipped ligature, bleeding from an anastomosis or diffuse hemorrhage from the retroperitoneal operation field, most likely caused by underlying coagulopathy, frequently seen in jaundiced patients (36,37). Late hemorrhage, occurring 1-3 weeks after surgery, is often caused by an anastomotic leak with erosion of retroperitoneal vessels (38) with mortality rates from 15%to 58% (39,40). Other causes of late hemorrhage are pseudoaneurysm and bleeding from the pancreaticojejunostomy. Management includes completion pancreatectomy or formation of pancreatic neoanastomosis (36). Other, not so common, complications are cholangitis, colonic and biliary fistulas. Within the systemic complications group, cardiopulmonary and neurological complications prevail (34,36). Over the years the most significant pancreaticoduodenectomy complication was the development of pancreatic leak and fistula (33,41,42) due to its frequency of occurrence and high mortality. However, with the refinement of surgical techniques, improved post-operative intensive care and concentration of patients in high-volume centres decreased mortality, this also resulted in decline of pancreatic fistula incidence. Depending on the definition used, the incidence of pancreatic fistula used to be 10-29% (43). Nowadays, according to the International Study Group Pancreatic Fistula Definition the incidence of pancreatic fistula is from 2% to 10% in the centres of excellence (30,34,41). The seriousness of pancreatic fistula can be seen in its possible consequences, such as septicaemia and hemorrhage, which makes it the leading risk factor for postoperative death, longer hospital stay and increased hospital costs after pancreaticoduodenectomy even today. Risks for developing the fistula can be divided into a few groups (Table 2). The first group is pancreas related. One of the most widely recognized risk factors is texture of the remnant pancreas; the relation between high rates of pancreatic fistula up to 25% (42,44-47) in the presence of soft pancreatic parenchyma has been repeatedly reported. The pancreatic duct size has been implicated as another relevant factor. Pancreatic duct diameter under 3 mm is related to a significantly higher risk of pancreatic fistula development (42,44,46,47). Pancreatic fistula development is also predisposed by pancreatic pathology: ampullary, bile duct, duodenal carcinoma and cystic neoplasms are correlated with an increased risk of pancreatic fistula (48,49). The second group of risk factors are patient related, including male sex, advanced age (older than 70) (48,50), cardiovascular disease probably due to poor blood supply of anastomosis (30), duration of jaundice (51). The last group is procedure related and includes a type of pancreaticodigestive anastomosis, use of somatostatin, surgeon’s experience and increased operative blood loss (20,21,23,24,30,43-47,52).

Full table

Prevention of complications

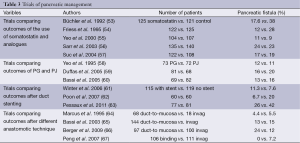

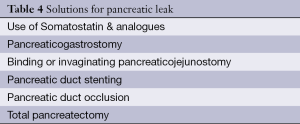

A great deal of research has been conducted over the years aimed at decreasing the risk of pancreatic fistula occurrence (Table 3). It has focused on the influence that somatostatin, pancreatic duct stenting and pancreatic occlusion have on the reduction of PF rate. In addition, a number of studies have become available which compare pancreaticogastric anastomosis versus pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and different pancreaticojejunal anastomotic technique and their influence on frequency of PF occurrence (Table 4).

Full table

Full table

Somatostatin and analogues

Octreotide is a synthetic long acting analogue of somatostatin, a potent inhibitor of pancreatic endocrine and exocrine secretion, and gastric and enteric secretion as well. Somatostatin and its analogue are administered postoperatively as prophylaxis. The idea behind this is that the decrease of pancreatic secretion would result in the pancreatic fistula prevention. A number of RTC have examined the benefit of somatostatine in pancreatic leakage prevention, but the results were inconsistent (68). In 2005, Connor conducted meta-analyses of ten RTCs which showed benefits of the use of somatostatin and its analog octreotide in reducing the rate of biochemical fistula formation, pancreas-specific complications and total morbidity. The incidence of clinical anastomotic disruption and mortality rate was not reduced (69). Cochrane Database Systematic Review from 2013 involved 2,348 patients in 21 trials. Conclusion drawn from it was that there was no significant difference in postoperative mortality, reoperation rate or hospital stay between the group of patients who were administered prophylactic somatostatin or its analogue and the group which received either placebo or nothing at all. In the somatostatin analogue group, the incidence of pancreatic fistula was lower, as was the overall number of patients with postoperative complications. On the other hand, when only patients with clinically significant fistulas were considered, there was no relevant difference between the groups. Based on the current available evidence, somatostatin and its analogues are recommended for routine use in people undergoing pancreatic resection (70).

Duct stenting

Internal, transanastomotic stent diverts the pancreatic juice from the anastomosis, and enables easier placement of sutures reducing the risk of iatrogenic duct occlusion. Its drawbacks are possibility of migration of the stent and occlusion which may lead to pancreatic fistula formation. There are not enough studies on internal stenting and their results have been contradictory (71,72). RTC from Winter et al. (61), involving 234 patients, demonstrated that internal duct stenting did not reduce the rate or the severity of pancreatic fistulas. The pancreatic fistula rates were 11.3% in patients with internal stent and 7.6% in patients without internal pancreatic stent. External stent has the possibility of a complete diversion of the pancreatic juice away from the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis which prevents the activation of pancreatic enzymes by bile. The RTC by Poon et al., involving 120 patients, showed that the external stent group pancreatic fistula rate was significantly lower (6.7%) compared to the group which did not undergo the same procedure (20%) (62). In prospective multicenter randomized trial from Pessaux et al., it was shown that external drainage reduces pancreatic fistula rate (26% vs. 42%), morbidity and delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy in high risk patients (soft pancreatic texture and a nondilated pancreatic duct) (63). Cochrane database systematic Review from 2013 involved 656 patients in order to determine the efficacy of pancreatic stents, both external and internal, in preventing pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. The use of external or internal stents was not associated with a statistically significant change in incidence of pancreatic fistula, re-operation rate, length of hospital stay, overall complications and in-hospital mortality. In the subgroup analysis, it was found that the use of external stents is associated with lower incidence of pancreatic fistula, the incidence of complications and length of hospital stay. The review concludes that the external stenting can be useful, but further RCTs on the use of stents are recommended (73).

Pancreatojejunal anastomosis technique

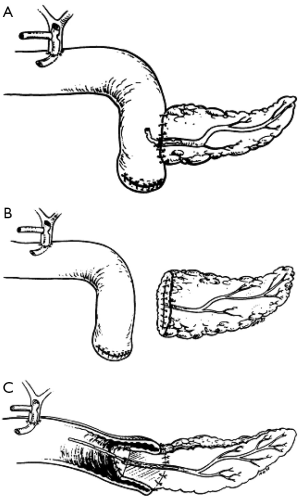

Ever since Whipple modified pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1942 by performing pancreaticojejunostomy instead of occlusion of pancreatic remnant, this type of anastomosis has been most commonly used for a reconstruction of pancreaticodigestive continuity. There have been further modifications over the years. For example, jejunal loop can be positioned in antecolic, retrocolic or retro-mesenteric fashion, or the isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy can be performed. The anastomosis can be performed as an end-to-end anastomosis with invagination of the pancreatic stump in the jejunum or as an end-to-side anastomosis with or without duct-to-mucosa suturing (Figure 1) (47,65,74,75). In 2002, Poon et al. su compared duct-to-mucosa with invagination anastomosis, and found that the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis was safer (49). In 2013, Bai et al. conducted a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing duct-to-mucosa (467 patients) and invagination pancreaticojejunostomy (235 patients). Pancreatic fistula rate, mortality, morbidity, reoperation and hospital stay were similar between techniques (76). Peng described a binding pancreaticojejunostomy technique with a pancreatic fistula rate of 0%. This was further validated in an RTC demonstrating that the binding pancreaticojejunostomy in comparison with end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy demonstrated significantly decreased postoperative pancreatic fistula rates, morbidity, mortality and shortened the hospital stay (67,77). However, multiple authors reported better results with binding or invaginating pancreaticojejunostomy technique in patients with soft pancreatic parenchyma and small size duct (42,64).

Type of pancreatic anastomosis

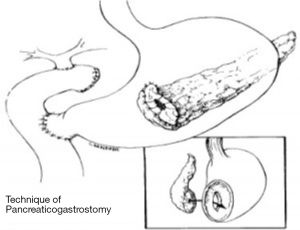

In 1946, Waugh and Clagett first introduced pancreaticogastrostomy in clinical practice (11) (Figure 2). There are several advantages of this anastomosis—the proximity of the stomach and the pancreas enables tension-free anastomosis, the excellent blood supply to the stomach enhances the anastomotic healing, the acidity of the stomach content inactivates pancreatic enzymes, and the lack of enterokinase in the stomach prevents the conversion of trypsinogen to trypsin and subsequent activation of the pancreatic enzymes, which reduces the risk of pancreatic leakage due to anastomosis autodigestion (78). Yeo et al. were first to conduct prospective randomized trial comparing pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticogastrostomy, but this trial failed in finding a significant difference in pancreatic fistula incidence (58). Statistically relevant difference regarding pancreatic fistula rates, postoperative complications or mortality has not been found in two RTCs from Duffas et al. (59) and Bassi et al. (60) as well. In 2014 Menahem et al. published their meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials, involving 562 patients with pancreaticogastrostomy and 559 patients with pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. The pancreatic fistula rate was significantly lower in the PG group (11.2%) then in the PJ group (18.7%). The biliary fistula rate was also significantly lower in the PG group (2% vs. 4.8%) (79). Liu et al. dealt with the same RTCs, but focused also on morbidity, mortality, hospital stay, reoperation and haemorrhage and intra-abdominal fluid collection. As well as having lower incidence of pancreatic and biliary fistula, the PG group showed a significantly lower incidence of intra-abdominal fluid collection and shorter hospital stay (80).

Duct occlusion

In 1935 Whipple reported on the first series of results after pancreaticoduodenectomy, at which time he did not anatomize pancreas with digestive tract. Since there was a high PF incidence rate, he abandoned the aforementioned concept and implemented pancreaticojejunostomy as a standard part of surgical procedure. Where there was suture ligation of the pancreatic duct, without anastomosis, the rates of pancreatic fistulas was as high as 80% (64,81,82). In a randomized controlled trial, conducted by Tran et al., involving 86 patients with duct occlusion and 83 patients with pancreaticojejunostomy, it was revealed that the da ductal occlusion group had a significantly higher pancreatic fistula rate (17% vs. 5%), but it failed to show any relevant difference regarding other postoperative complications, mortality and exocrine insufficiency. After 3 and 12 months, there were significantly more patients with diabetes mellitus in the ductal occlusion group (83). Occlusion of the main pancreatic with fibrin glue was also abandoned (83,84) based on results from several RCTs because of high fistula rates and higher incidence of postoperative diabetes mellitus (83,85).

Treatment

Surgical interventions for complications after pancreatoduodenectomy are nowadays rare, as low as 4% in centers of excellence (33,34) and 85-90% of patients with pancreatic fistula can be treated conservatively by means of fluid management, parenteral nutrition, suspension of oral intake and antibiotics administration. Lower percentage of surgical interventions can also be attributable to more advanced radiologic interventions for intrabdominal fluid collections, fistulas and bleeding. Indications for surgical intervention are clinical deterioration of the patient, disruption of pancreatic anastomosis, signs of spreading peritonitis, abdominal abscess, haemorrhage, and wound dehiscence. Delayed hemorrhage can be managed, if a patient is stable, by angiographic embolization of the bleeding vessel. In the remaining number of cases, emergency surgery is indicated (86,87). The type of surgical procedure depends on the underlying cause, and includes procedures such as peripancreatic drainage, control of hemorrhage, disruption of the pancreatic anastomosis without a new anastomosis or a conversion in another type of pancreatic anastomosis and a completion pancreatectomy (68,78).

Completion pancreatectomy has nowadays become a rare procedure, owing to improvements in conservative treatment and radiologic interventions. Completion pancreatectomy is indicated in patients with pancreatic anastomotic leak accompanied by sepsis or bleeding (88). Owing to the seriousness of the patient’s condition, this procedures postoperative mortality is between 38% and 52% (89,90).

Total pancreatectomy

Total pancreatectomy was first performed in 1943 by Rockey (91), but the patient died soon after it. In 1944 Priestley performed the first successful total pancreatectomy (8). During the 1950’s this procedure was popularised by Ross (92) and Porter (93) who considered it to be safer than pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatojejunostomy, because pancreatic anastomosis related morbidity and mortality was avoided. Because of high local recurrence rates and poor long-term survival after Whipple operation, combined with the erroneous belief that pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a multicentric disease, total pancreatectomy was thought to be an oncologically more radical procedure (94,95). Later reports revealed disadvantages of this procedure: long-term survival after total pancreatectomy was similar or lower than after pancreatoduodenectomy (96), morbidity and mortality were as high as 37% (95-97), with obligatory development of brittle diabetes mellitus and exocrine insufficiency. Development of steatohepatitis with progressive liver failure (98) is another potential long-term complication. Without advantages of oncologic radicality and with diabetes mellitus and malabsorption difficult to control, total pancreatectomy was abandoned for treating pancreatic tumors.

Number of total pancreatectomy procedures has been on the rise over the last two decades, for which several reasons can be named. Concentrating patients in high-volume centres and enhancements in surgical techniques have resulted in morbidity and mortality decline, the rates of which are now as low as 35% and 5% respectively (99-101) and are comparable to those following pancreatoduodenectomy. The second reason lies in the development of novel insulin formulations and better pancreatic enzyme preparations. While exocrine insufficiency can be relatively easily managed using pancreatic enzyme supplements, the control of endocrine insufficiency demands intensive insulin programmers, extensive patient education and continuing care (102). Total pancreatectomy is followed by not only insulin insufficiency, but also of glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide insufficiency, which leads to development of diabetes mellitus with tendencies to severe hypoglycemia. However, with intensive insulin programmers utilizing multiple daily insulin injections or pumps, and with glucagon rescue therapy, glycemic control can be achieved with satisfactory levels of HBA1c, similar to those in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes from other causes (99,102-104) and quality of life comparable to those of the patients after PPPD (99,100).

The third reason is the existence of broader spectre of indications which now include in situ neoplasia with malignant potential such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and multifocal islet cell neoplasm; hereditary pancreatitis and familiar pancreatic cancer syndromes. Other indications include locally advanced or multicentric pancreatic adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, metastases in the pancreas, end-stage chronic pancreatitis with disabling pain, trauma, unsafe pancreatic anastomosis and completion pancreatectomy after dehisced pancreato-enteric anastomosis (98,99,102).

Given that the postoperative total pancreatectomy morbidity and mortality outcomes do not differ significantly from those after pancreatoduodenectomy (17,33,34,98,99), and the quality of life is fairly acceptable, there are no restrictions for performing total pancreatectomy on patients with indication for total pancreatectomy (99,101).

Discussion

After decreasing a 30-day mortality rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy to about 5%, surgeons have now focused their efforts on reducing morbidity, which is still as high as 30-60% (17,105-107). This mainly concerns reduction in incidence of pancreatic fistula, which is regarded the main cause of other frequent complications such as delayed gastric emptying, septic complications and intraabdominal haemorrhage.

Ever since Whipple’s first pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy, surgeons have paid special attention to anastomosis between pancreatic remnant and digestive tract. In highly specialized centres pancreatic fistula incidence is from 0 to 18% (108), with death rate of 5%. Among the reports classifying pancreatic fistulas as A, B or C, following ISGPF grading system, incidence of grade C pancreatic fistulas was 2-5% (109-111). Grade C pancreatic fistulas were associated with sepsis from intrabdominal collections and bleeding, with high reoperation rate, prolonged length of hospital stay and with mortality rates from 35-40%. Soft pancreatic parenchyma is the most widely recognized risk factor for pancreatic fistula (112,113), along with three other relevant factors: duct size smaller than 3 mm, excessive intraoperative blood loss and specific pathology: ampullary, duodenal, cystic or islet cell neoplasms (111). The question is what to do when one or more risk factors for development of pancreatic fistula are present. There are multiple factors that will influence a decision which procedure to perform. First, to preserve a sufficient endocrine pancreatic function, approximately 50% of alpha and beta cells must be preserved (114). Alpha and beta cells are located predominately in the tail of the pancreas (115), so, theoretically, classical pancreaticoduodenectomy procedure should not cause endocrine insufficiency. When a pancreatic duct is occluded, without pancreatic anastomosis, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency will surely develop. Besides exocrine insufficiency, there is a significantly higher incidence of diabetes mellitus in patients with chemical occlusion of pancreatic duct in comparison with patients with a pancreaticojejunostomy (83). On the other hand, exocrine insufficiency will also develop in 9-20% of patients after Whipple procedure (116,117). The underlying cause are probably stenosis of pancreatic anastomosis and postoperative inflammation of the pancreas and fibrosis of pancreatic parenchyma (118,119). Other factors include patient’s preexisting diabetes mellitus or exocrine insufficiency, patient’s overall health and performance status and patient’s compliancy. A surgeon has several possibilities. First option is to perform a pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatogastrojejunostomy, because of the lower incidence of pancreatic fistula with this type of anastomosis (79,80) or pancreatoduodenectomy with invagination pancreaticojejunostomy, recommended by a number of authors in case of soft pancreatic parenchyma and small pancreatic duct (67,113). Second option is also pancreatoduodenectomy, but with occlusion of the pancreatic remnant, either by ligation of the main pancreatic duct or by occlusion of the main pancreatic duct by Neoprene, Ethibloc or fibrin glue injection. This procedure is related to a higher incidence of pancreatic fistula, but with more benign clinical course, because pancreatic enzymes are not activated. The last option is total pancreatectomy for initial treatment of patients with multiple risk factors. With this procedure potential risks of a pancreatic fistula are eliminated, but with establishment of a total pancreatic state. Because of glycemic instability, predisposition for severe, life-threating hypoglycemia, and need for close glucose monitoring and intense insulin programme, patient’s compliance after total pancreatectomy is essential.

When a surgeon encounters such a significant problem, the decision about proper surgical management can be difficult to make. Besides purely technical challenges, patients overall health status, existing comorbidities, pancreas pathology and expected survival are crucial in the decision-making process.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2011, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available online: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No.11 (Internet). Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available online: http://globocan.iarc.fr

- Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2014. Ann Oncol 2014;25:1650-6. [PubMed]

- Gaedcke J, Gunawan B, Grade M, et al. The mesopancreas is the primary site for R1 resection in pancreatic head cancer: Relevance for clinical trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2010;395:451-8. [PubMed]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas: 201 patients. Ann Surg 1995;221:721-31. [PubMed]

- Kausch W. Das karzinom der papilla duodeni und seine radikale entfernung. Beitrage zur Klinischen Chirurgie 1912;78:29-33.

- Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg 1935;102:763-79. [PubMed]

- Priestley JT, Comfort MW, Radcliffe J. Total Pancreatectomy for Hyperinsulinism Due to an Islet- Cell Adenoma: Survival and Cure at sixteen months after operation, presentation of Metabolic studies. Ann Surg 1944;119:211-21. [PubMed]

- Traverso LW, Longmire WP Jr. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1978;146:959-62. [PubMed]

- Whipple AO. Observations on radical surgery for lesions of pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1946;82:623-31. [PubMed]

- Waugh JM, Clagett OT. Resection of the duodenum and head of the pancreas for carcinoma; an analysis of thirty cases. Surgery 1946;20:224-32. [PubMed]

- Gilsdorf RB, Spanos P. Factors influencing morbidity and mortality in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1973;177:332-7. [PubMed]

- Monge JJ, Judd ES, Gage RP. Radical pancreatoduodenectomy: a 22-year experience with the complications, mortality rate, and survival rate. Ann Surg 1964;160:711-22. [PubMed]

- Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, et al. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2004;91:586-94. [PubMed]

- Beger HG, Rau B, Gansauge F, et al. Treatment of pancreatic cancer: Challenge of the facts. World J Surg 2003;27:1075-84. [PubMed]

- American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: epidemiology, diagnosis, and teratment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 1999;117:1463-84. [PubMed]

- Büchler MW, Wagner M, Schmied BM, et al. Changes in morbidity after pancreatic resection: toward the end of completion pancreatectomy. Arch Surg 2003;138:1310-4; discussion 1315. [PubMed]

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the Unites States. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1128-37. [PubMed]

- McPhee JT, Hill JS, Whalen GF, et al. Perioperative mortality for pancreatectomy: a national perspective. Ann Surg 2007;246:246-53. [PubMed]

- Schmidt CM, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a 20-year experience in 516 patients. Arch Surg 2004;139:718-25; discussion 725-7. [PubMed]

- assi C, Falconi M, Salvia R, et al. Management of complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high volume centre: results on 150 consecutive patients. Dig Surg 2001;18:453-7; discussion 458. [PubMed]

- Richter A, Niedergethmann M, Sturm JW, et al. Long-term results of partial pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head: 25-year experience. World J Surg 2003;27:324-9. [PubMed]

- Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, et al. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg 2006;244:10-5. [PubMed]

- Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. International study group on pancreatic fistula definition. Post- operative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13. [PubMed]

- Schäfer M, Müllhaupt B, Clavien PA. Evidence-based pancreatic head resection for pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2002;236:137-48. [PubMed]

- Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic resection in the 1990s. Arch Surg 1995;130:295-9; discussion 299-300. [PubMed]

- Patel AG, Toyama MT, Kusske AM, et al. Pylorus- preserving Whipple resection for pancreatic cancer. Is it any better? Arch Surg 1995;130:838-42. [PubMed]

- Lin PW. Lin Yj. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 1999;86:603-7. [PubMed]

- van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Gulik TM, DeWitt LT, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy versus pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of 200 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg 1997;185:373-9. [PubMed]

- DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, et al. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: A novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2006;244:931-7; discussion 937-9. [PubMed]

- Matsumoto Y, Fuji H, Miura K, et al. Sucsessfull pancreatojejunal anastomosis for pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1992;175:555-62. [PubMed]

- Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM. Pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance and management. Am J Surg 1994;168:295-8. [PubMed]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg 1997;226:248-57; discussion 257-60. [PubMed]

- Büchler MW, Friess H, Wagner M, et al. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. Br J Surg 2000;87:883-9. [PubMed]

- Halloran CM, Ghaneh P, Bosonnet L, et al. Complications of pancreatic cancer resection. Dig Surg 2002;19:138-46. [PubMed]

- Ho CK, Kleeff J, Friess H, et al. Complications of pancreatic surgery. HPB 2005;7:99-108. [PubMed]

- Rumstadt B, Schwab M, Korth P, et al. Haemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1998;227:236-41. [PubMed]

- Brodsky JT, Turnbull AD. Arterial hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. The ‘sentinel bleed’. Arch Surg 1991;126:1037-40. [PubMed]

- van Berge Henegouwen MI, Allema JH, Van Gulik TM, et al. Delayed massive hemorrhage after pancreatic and billiary surgery. Br J Surg 1995;82:1527-31. [PubMed]

- Shankar S, Russell RC. Haemorrhage in pancreatic disease. Br J Surg 1989;76:863-6. [PubMed]

- Trede M, Saeger HD, Schwall G, et al. Resection of pancreatic cancer--surgical achievements. Langenbecks Arch Surg 1998;383:121-8. [PubMed]

- van Berge Henegouwen MI, de Witt LT, Van Gulik TM, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: drainage versus resection of the pancreatic remnant. J Am Coll Surg 1997;185:18-24. [PubMed]

- Bassi C, Butturini G, Molinari E, et al. Pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatic resection: the importance of definitions. Dig Surg 2004;21:54-9. [PubMed]

- Callery MP, Pratt WB, Vollmer CM Jr. Prevention and management of pancreatic fistula. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:163-73. [PubMed]

- Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, et al. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:2456-61. [PubMed]

- Shrikhande SV, D’Souza MA. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: evolving definitions, preventive strategies and modern management. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:5789-96. [PubMed]

- Lai EC, Lau SH, Lau WY. Meassures to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comprehensive review. Arch Surg 2009;144:1074-80. [PubMed]

- Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:951-9. [PubMed]

- Poon RT, Lo SH, Fong D, et al. Prevention of pancreatic anastomosis leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2002;183:42-52. [PubMed]

- Matsusue S, Takeda H, Nakamura Y, et al. A prospective analysis of the factors influencing pancreaticojejunostomy performed using a single method, in 100 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Surgery Today 1998;28:719-26. [PubMed]

- Yeh TS, Jan YY, Jeng LB, et al. Pancreaticojejunal anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy--multivariate analysis of perioperative risk factors. J Surg Res 1997;67:119-25. [PubMed]

- Lowy AM, Lee JE, Pisters PW, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of octreotide to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignant disease. Ann Surg 1997;226:632-41. [PubMed]

- Büchler M, Friess H, Klempa I, et al. Role of octreotide in the prevention of postoperative complications following pancreatic resection. Am J Surg 1992;163:125-30; discussion 130-1. [PubMed]

- Friess H, Beger HG, Sulkowski U, et al. Randomized controlled multicenter study of the prevention of complications by octreotide in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1995;82:1270-3. [PubMed]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemos KD, et al. Does prophylactic octreotide decrease the rates of pancreatic fistula and other complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized placebo- controlled trial. Ann Surg 2000;232:419-29. [PubMed]

- Sarr MG; Pancreatic Surgery Group. The potent somatostatin analogue vapreotide does not decrease pancreas-specific complications after elective pancreatectomy: a prospective, multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:556-64; discussion 564-5; author reply 565. [PubMed]

- Suc B, Msika S, Piccinini M, et al. Ocreotide in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications following elective pancreatic resection: a prospective, multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg 2004;139:288-94. [PubMed]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM, et al. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreatcojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1995;222:580-8. [PubMed]

- Duffas JP, Suc B, Msika S, et al. French association for Research in Surgery. A controlled randomized multicenter trial of pancreatogastrostomy or pancreatojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2005;189:720-9. [PubMed]

- Bassi C, Falconi M, Molinari E, et al. Reconstruction by pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy following pancreatectomy: results of a comparative study. Ann Surg 2005;242:767-71. [PubMed]

- Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, et al. Does pancreatic duct stenting decrease the rate of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1280-90. [PubMed]

- Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. External drainage of pancreatic duct with a stent to reduce leakage rate of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 2007;246:425-33; discussion 433-5.. [PubMed]

- Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Mariette C, et al. External pancreatic duct stent decreases pancreatic fistula rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy: prospective multicenter randomized trial. Ann Surg 2011;253:879-85. [PubMed]

- Marcus SG, Cohen H, Ranson JH. Optimal management of the pancreatic remnant after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1995;221:635-45; discussion 645-8. [PubMed]

- Bassi C, Falconi M, Molinari E, et al. Duct-to-mucosa versus end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction after pancreaticojduodenectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery 2003;134:766-71. [PubMed]

- Berger AC, Howard TJ, Kennedy EP, et al. Does type of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy decrease rate of pancreatic fistula? A randomized, prospective, dual-institution trial. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:738-47. [PubMed]

- Peng SY, Wang JW, Lau WY, et al. Conventional versus binding pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 2007;245:692-98. [PubMed]

- Machado NO. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: Definitions, Risk Factors, Preventive Measures, and Management- review. Int J Surg Onc 2012;2012:1-10.

- Connor S, Alexakis N, Garden OJ, et al. Meta- analysis of the value of somatostatin and its analogues in reducing complications associated with pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg 2005;92:1059-67. [PubMed]

- Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Fusai G, et al. Somatostatin analogues for pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD008370. [PubMed]

- Yoshimi F, Ono H, Asato Y, et al. Internal stenting of the hepaticojejunostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy to promote earlier discharge from hospital. Surg Today 1996;26:665-7. [PubMed]

- Imaizumi T, Hatori T, Tobita K, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy using duct-to-mucosa anastomosis without a stenting tube. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006;13:194-201. [PubMed]

- Dong Z, Xu J, Wang Z, et al. Stents for the prevention of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;6:CD008914. [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Mokadam NA, et al. Prospective trial of a blood supply-based technique of pancreaticojejunostomy: effect on anastomotic failure in the Whipple procedure. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:746-58; discussion 759-60. [PubMed]

- Z’graggen K, Uhl W, Friess H, et al. How to do a safe pancreatic anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2002;9:733-7. [PubMed]

- Bai XL, Zhang Q, Masood N, et al. Duct-to-mucosa versus invagination pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:4340-7. [PubMed]

- Peng S, Mou Y, Cai X, et al. Binding pancreaticojejunostomy is a new technique to minimize leakage. Am J Surg 2002;183:283-5. [PubMed]

- Crippa S, Salvia R, Falconi M, et al. Anastomotic leakage in pancreatic surgery. HPB 2007;9:8-15. [PubMed]

- Menahem B, Guittet L, Mulliri A, et al. Pancreaticogastrostomy is superior to pancreaticojejunostomy for prevention of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. Ann Surg 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Liu FB, Chen JM, Geng W, et al. Pancreaticogastrostomy is associated with significantly less pancreatic fistula than pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta- analysis of seven randomized controlled trials. HPB (Oxford) 2014. [Epub ahead of print].

- Sakorafas GH, Friess H, Balsiger BM, et al. Problems of recontruction during pancreatoduodenectomy. Dig Surg 2001;18:363-9. [PubMed]

- Papachristou DN, Fortner JG. Pancreatic fistula complicating pancreatectomy for malignant disease. Br J Surg 1981;68:238-40. [PubMed]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM, et al. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1995;222:580-8; discussion 588-92. [PubMed]

- Suc B, Msika S, Fingerhut A. French association for Research in Surgery. Temporary Fibrin Glue Occlusion of the main pancreatic duct in the prevention of intraabdominal complications after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg 2003;237:57-65. [PubMed]

- Konishi T, Hiraishi M, Kubota K, et al. Segmental occlusion of the pancreatic duct with prolamine to prevent fistula formation after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg 1995;221:165-70. [PubMed]

- de Castro SM, Kuhlmann KF, Busch OR, et al. Delayed massive hemorrhafe after pancreatic and biliary surgery. Embolization or surgery? Ann Surg 2005;241:85-91. [PubMed]

- Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg 2007;246:269-80. [PubMed]

- Tamijmarane A, Ahmed I, Bhati CS, et al. Role of compoletion pancreatectomy as a damage control option for post- pancreatic surgical complications. Dig Surg 2006;23:229-34. [PubMed]

- Gueroult S, Parc Y, Duron F, et al. Completion pancreatectomy for postoperative peritonitis after pancreaticoduodenectomy: early and late outcome. Arch Surg 2004;139:16-9. [PubMed]

- Wittmann DH, Schein M, Condon RE. Management of secondary peritonitis. Ann Surg 1996;224:10-8. [PubMed]

- Rockey EW. Total pancreatectomy for carcinoma. Case report. Ann Surg 1943;118:603-11. [PubMed]

- Ross DE. Cancer of the pancreas; a plea for total pancreatectomy. Am J Surg 1954;87:20-33. [PubMed]

- Porter MR. Carcinoma of the pancreatico-duodenal area; operability and choice of procedure. Ann Surg 1958;148:711-23. [PubMed]

- ReMine WH, Priestley JT, Judd ES, et al. Total pancreatectomy. Ann Surg 1970,172:595-604. [PubMed]

- Sarr MG, Behrns KE, van Heerden JA. Total pancreatectomy. An objective analysis of its use in pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:418-21. [PubMed]

- Grace PA, Pitt HA, Tompkins RK, et al. Decreased morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 1986;151:141-9. [PubMed]

- McAfee MK, van Heerden JA, Adson MA. Is proximal pancreatoduodenectomy with pyloric preservation superior to total pancreatectomy? Surgery 1989;105:347-51. [PubMed]

- Heidt DG, Burant C, Simeone DM. Total pancreatectomy: Indications, operative technique, and postoperative sequelae. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:209-16. [PubMed]

- Müller MW, Friess H, Kleeff J, et al. Is there still a role for total pancreatectomy? Ann Surg 2007;246:966-74; discussion 974-5. [PubMed]

- Billings BJ, Christein JD, Harmsen WS, et al. Quality-of-life after total pancreatectomy: is it really that bad on long-term follow-up? J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:1059-66; discussion 1066-7. [PubMed]

- Hartwig W, Gluth A, Hinz U, et al. Total pancreatectomy for primary pancreatic neoplasms: Renaissance of an unpopular operation. Ann Surg 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Parsaik AK, Murad MH, Sathananthan A, et al. Metabolic and target organ outcomes after total pancreatectomy: Mayo Clinic experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Clinical Endocrinology 2010;73:723-31. [PubMed]

- Jethwa P, Sodergren M, Lala A, et al. Diabetic control after total pancreatectomy. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:415-9. [PubMed]

- MacLeod KM, Hepburn DA, Frier BM. Frequency and morbidity of severe hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Diabet Med 1993;10:238-45. [PubMed]

- Neoptolemos JP, Russell RC, Bramhall S, et al. Low mortality following resection for pancreatic and periampullary tumours in 1026 patients: UK survey of specialist pancreatic units. UK Pancreatic Cancer Group. Br J Surg 1997;84:1370-6. [PubMed]

- Stojadinovic A, Brooks A, Hoos A, et al. An evidence-based approach to the surgical management of resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:954-64. [PubMed]

- Cooperman AM, Schwartz ET, Fader A, et al. Safety, efficacy, and cost of pancreaticoduodenal resection in a specialized center based at a community hospital. Arch Surg 1997;132:744-7; discussion 748. [PubMed]

- Schäfer M, Müllhaupt B, Clavien PA. Evidence-based pancreatic head resection for pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2002;236:137-48. [PubMed]

- Fuks D, Piessen G, Huet E, et al. Life-threatening postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade C) after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, prognosis and risk factors. Am J Surg 2009;197:702-9. [PubMed]

- Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T, et al. Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg 2007;245:443-51. [PubMed]

- Callery MP, Wande BP, Kent TS, et al. Prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:1-14. [PubMed]

- Mathur A, Pitt HA, Marine M, et al. Fatty pancreas: a factor in postoperative pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg 2007;246:1058-64. [PubMed]

- Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, et al. Selection of pancreaticojejunostomy techniques according to pancreatic texture and duct size. Arch Surg 2002;137:1044-7; discussion 1048. [PubMed]

- Schrader H, Menge BA, Breuer TGK, et al. Impaired Glucose-Induced Glucagon Suppression after partial pancreatectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:2857-63. [PubMed]

- Wittingen J, Frey CF. Islet concentration in the head, body, tail and uncinate process of the pancreas. Ann Surg 1974;179:412-4. [PubMed]

- Idezuki Y, Goetz FC, Lillehei RC. Late effect of pancreatic duct ligation on beta cell function. Am J Surg 1969;117:33-39. [PubMed]

- Shankar S, Theis B, Russell RC. Management of the stump of the pancreas after distal pancreatic resection. Br J Surg 1990;77:541-44. [PubMed]

- Tran TC, van’t Hof G, Kazemier G, et al. Pancreatic fibrosis correlates with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatoduodenectomy. Dig Surg 2008;25:311-8. [PubMed]

- Nordback I, Parviainen M, Piironen A, et al. Obstructed pancreaticojejunostomy partly explains exocrine insufficiency after paancreatic head resection. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:263-70. [PubMed]